Stop us if you’ve heard this one before: a ski area invests in the latest and greatest new lift, welcomes an influx of new guests eager to try it out and then discovers it’s not equipped to handle the resulting surge in attendance.

While it might sound like a punchline, it’s no laughing matter, says the founder of a Swiss-based consulting company that advises ski areas around the globe on how they can safely increase capacity on their hills.

Beat von Allmen is the founder of Alpentech, which has advised ski areas in Canada, the U.S., China, Argentina, France and his native Switzerland on how they can make their facilities work better and reduce crowding. A member of the Swiss ski team at the 1964 Winter Olympics, his consulting work earned him a Ski Area Design Award from the National Ski Areas Association (NSAA).

Von Allmen says one of the most common mistakes ski facilities make is installing a new lift without considering the implications it may have for a hill’s terrain or on the flow of people using that hill. “Oftentimes they don’t look at the overall picture first. They just say, ‘Let’s put this six pack [lift] over here,’” he said. “They don’t realize it shifts the traffic and [creates] new conditions. They should really look at the whole mountain and the impact it can have before they build a new lift.”

The risk in not looking at the bigger picture can be two-fold, von Allmen says. First, it can overload the popular runs and increase the risk of collisions. Second, it can rob skiers of the joy they feel based on a freedom of space heading downhill. “It is common to forget the intent [is] to enjoy the slopes rather than ride a lift,” he said.

Part of the problem is that the permitting process for replacing a lift on the same alignment is often automatically approved while any small trail improvements receive much greater scrutiny, von Allmen says. Historically, ski areas were built for slow fixed double chairs and are modified with fast detachable lifts requiring vastly bigger trail capacities.

The demand for the type of work von Allmen’s company performs is only going to increase as more resorts invest in high-speed or high-capacity lifts.

This “over-lifting” is quite common at many ski areas and skier flow begins to “stutter” at common bottlenecks as a result. The problem, von Allmen says, is that trail capacity often isn’t recognized as a limit at some ski areas. His advice to ski facilities that are looking to expand or upgrade their lift system is to look at where they have additional trail capacity before they decide where to place a new lift system.

If facility managers decide to widen or redesign a trail to accommodate more users, von Allmen says the first thing they should do is consult the ski patrol and any ski schools that use the area, and ask their opinion on any spots that might cause collisions, including blind spots or locations that are congested. That feedback can be used to determine a priority list for trail improvements.

Von Allmen says the French government deserves a tip of the cap for being forward-thinkers with ski operations planning in the 1960s and 1970s. Many of the ideas they came up with are still used, including the rule-of-thumb that there should be 10 meters of trail capacity for every 100 meters of uphill capacity.

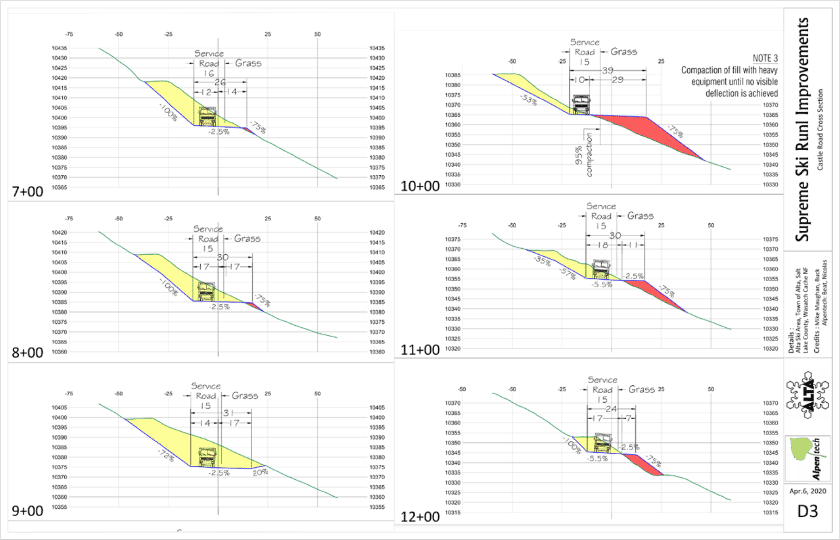

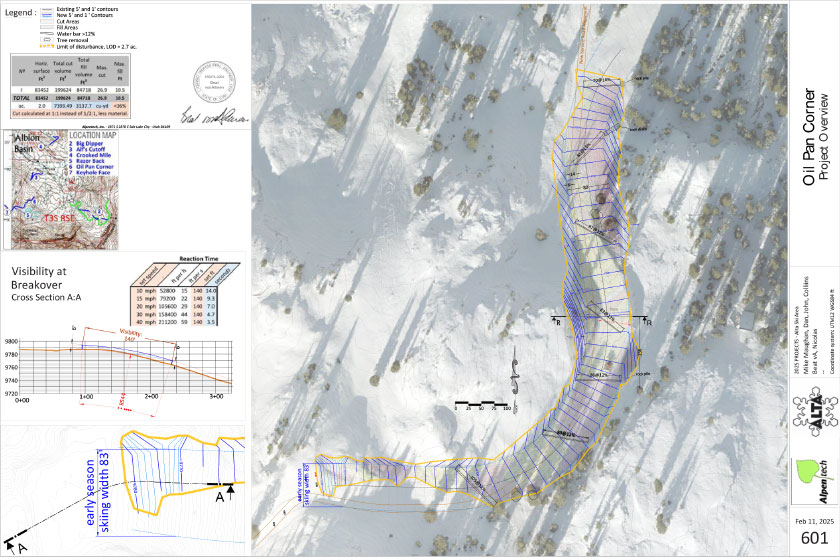

One of the most recent trail expansion projects von Allmen and his company were involved in was at Alta Ski Area, located in the Wasatch Mountain Range near Salt Lake City, Utah, which is making several improvements for the upcoming season to accommodate intermediate and advanced skiers. Alpentech helped in the design of seven projects which are part of the planned improvements at Alta.

That includes redesigning a race course entry that will give grooming machine operators better access to the run, allowing them to create additional capacity for skiers. The next project involved redesigning Alta’s Big Dipper intermediate ski run to make it less steep and provide an additional run. They also designed changes to Alf’s Cutoff to increase visibility and make it easier to access the lodge’s restaurant.

Historically, ski areas were built for slow fixed double chairs and are modified with fast detachable lifts requiring vastly bigger trail capacities.

In addition, Alpentech helped to reconfigure the Crooked Mile to mitigate avalanche closures and create a bypass for beginner traffic. The resort’s Razorback run is undergoing some terrain changes that will provide improved snow grooming access and reduce skier congestion on the trail. The company also made plans to widen Oil Pan Corner to make it larger and create a uniform trail width. The final project was removing a blind spot from the Keyhole Face ski run.

Von Allmen says creating additional capacity at any ski area is always something of a “balancing act.” While bringing in more skiers is good news for a resort’s bottom line, it can also create safety issues if the changes aren’t implemented correctly.

While it’s important to try and maintain a trail’s aesthetics and flow as part of any expansion, von Allmen says that sometimes compromises must be made. He points out that because such projects often involve cutting trees and moving material laterally, changing the look or feel of a trail can be difficult to avoid. One way of mitigating that is by merging trails and creating a meadow-like environment, or do widen alternate trail sides.

Von Allmen is hopeful that ski areas are catching on to the idea that the ski experience can be improved by making alterations to trails at a fraction of the cost of installing a new state-of-the-art lift. In fact, he says that such improvements could help lure back some skiers who quit the sport out of frustration over trail overcrowding or fear of collisions.

The demand for the type of work von Allmen’s company performs is only going to increase as more resorts invest in high-speed or high-capacity lifts. This past year Alpentech had to tell clients it couldn’t take on any new projects because it was fully booked.

“I’m positive [demand will continue to increase],” he said. “Ski areas have lost a number of skiers. If trails are congested, who in the heck wants to be there anymore? Ski areas are being a little more cautious with where they spend their money now. If you address the 10% cost of a [trail] improvement … maybe, you’ll have as much of a good result as having a new lift with an overrun trail system.”